|

Winter 2000 (8.4)

Pages

38-39

Making Houses into Homes

Eni and

UNHCR Team up to Help Refugees

Above: Refugee tent camps in

Sabirabad supplied by the Norwegian Red Cross and funded by the

Norwegian government. The tents, intended as temporary shelter,

have long since worn out and replaced by mud-brick shelters that

were built by the refugees themselves. Photo: IFRCRC, December

1994.

Azerbaijan

has approximately 1 million refugees as a result of the Nagorno-Karabakh

war with Armenia. Many of them fled their homes with just a few

moments' notice, grabbing the hands of their children and running

out the door with nothing but the clothes on their backs. In

towns like Kalbajar, 3,000 meters up in the Caucasus mountains,

they trekked through mountain passes in the snow for several

days seeking refuge. Some died from over-exposure to the cold;

others still suffer from consequences of frostbite.

Azerbaijan's refugees still dream of returning home despite the

fact that it's been nearly nine years now that some of them have

been living in temporary quarters - tent camps, abandoned buildings,

railroad boxcars and underground dugouts. Azerbaijan's governmental

officials insist that one of the conditions of peace with Armenia

must be that these refugees can return to their homelands.

Left: Many refugees moving to the new camp

at Beylagan had been living in buildings originally intended

for sheep and cattle. Note the piles of sheep manure carefully

gathered to be used as cooking fuel. International. Left: Many refugees moving to the new camp

at Beylagan had been living in buildings originally intended

for sheep and cattle. Note the piles of sheep manure carefully

gathered to be used as cooking fuel. International.

In the meantime, Eni, through its subsidiary Agip Azerbaijan,

is funding a $2.25 million project to help provide two new settlements

for Azerbaijan's refugees - for approximately 400 families in

the towns of Khanlar and Beylagan. UNHCR is administrating the

project under the direction of Didier Laye.

_____

Finally, moving day had arrived. Refugee families packed up their

meager possessions - blankets, clothes, stuffed mattresses, a

few pots, plates and utensils - and headed to Beylagan, a new

settlement in central Azerbaijan. After seven years as refugees,

they still didn't have much in the way of material goods, but

many families carried with them small pots of plants - flowers

and herbs like mint and basil. Some they would put in their windows.

Some they would plant outside.

"It's quite natural," says Vugar Abdusalimov,

Public Information Officer for UNHCR, which organized the shelters'

construction. "Even in the worst conditions, you see refugees

trying to plant herbs and flowers - trying to create a touch

of color. People want to ornament their lives despite the misery

they live in. It seems innate - this quest for beauty and aesthetics."

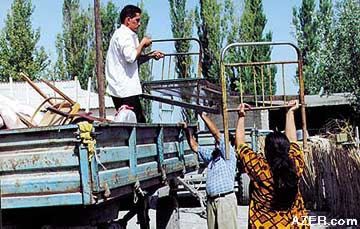

Left: Moving day in October 2000; most families

don't have much to show in terms of material possessions for

the past eight years living as refugees. Left: Moving day in October 2000; most families

don't have much to show in terms of material possessions for

the past eight years living as refugees.

Restored Dignity

It's not like these new shelters are luxurious - or even all

that comfortable - but they represent a measure of hope for refugees

who have been living in appalling conditions ever since they

left their native lands during the Armenian invasion.

"More than anything else," Vugar says, "it seems

to be a question of dignity. Some of these people have literally

been living in pig sties and stables for cattle. Many refugees

have told me that they feel ashamed because they can't build

a house for their family. Whenever a child gets sick, the father

starts blaming himself, saying, 'I couldn't provide a house for

my family; we left our home behind in an area that is now occupied

by enemy soldiers.' The fact that they now own something - a

house - is very important psychologically."

This new sense of pride is something refugees can build on, he

says. "We are speaking about people who are trying to create

a future for themselves. Again, bear in mind that the ultimate

decision for these people will be the day when they are able

to go back home. But until then, we have to think about putting

these people in decent conditions and providing them with a setting

where they can live and send their children to school."

Left: Agip Azerbaijan funded UNHCR as the

umbrella organization to coordinate the $2.25 million project

which will house 400 families and an estimated 2,000 people in

two separate communities - Beylagan and Khanlar. Shelters were

constructed by Relief International Left: Agip Azerbaijan funded UNHCR as the

umbrella organization to coordinate the $2.25 million project

which will house 400 families and an estimated 2,000 people in

two separate communities - Beylagan and Khanlar. Shelters were

constructed by Relief International

Homes Left Behind

The refugees in the new Khanlar settlement come from the Kalbajar

region. Before the Nagorno-Karabakh war, Kalbajar was home to

about 60,000 Azerbaijanis.

"Kalbajar had a very beautiful landscape," says Abdusalimov,

"probably one of the best in Azerbaijan - mountains, forests,

springs. Some of the best spring water in Azerbaijan comes from

Kalbajar; it's called Istisu (Hot Springs)." The region

is also known for the longevity of its people, many of them living

past 100 years.

Maryam Fakhr-Brandt, the UNHCR Community Settlement Consultant

for this project, tells the story of the refugees' March 1993

flight from Kalbajar: "We heard about it from a woman who

had lived in Kalbajar with her brothers. Right before the Kalbajar

area was occupied [April 2], the people in her village were trying

to decide whether they should evacuate. Naturally, they didn't

want to leave, but the Azerbaijani army had already abandoned

its position, and the people were afraid that the Armenian soldiers

would soon occupy their town. No authority told them what to

do. There were only rumors flying around.

"The villagers

decided to leave. The woman's brothers told her to go on ahead

with some neighbors, and that they would join her later. Since

there were no vehicles to take, she left as quickly as possible

on foot. "The villagers

decided to leave. The woman's brothers told her to go on ahead

with some neighbors, and that they would join her later. Since

there were no vehicles to take, she left as quickly as possible

on foot.

Left: Keys for the brand-new

refugee shelters at Beylagan.

The road south to Aghdam was filled with soldiers, so the villagers

had to flee in the other direction - over a 3,000-meter mountain

- north towards Ganja. There was deep snow on the ground. Some

people died from over-exposure to the cold. This woman made it

to Barda, where her brothers finally caught up with her a week

later."

Meeting the Need

Ever since the Armenian occupation, many of Azerbaijan's 1 million

refugees have been living in miserable conditions: tent camps,

abandoned boxcars, the locker rooms under empty stadiums - even

sheds and buildings originally intended for cattle. Anything

to provide a roof over their heads.

To help improve the refugees' living situation, the Italian oil

and natural gas company Eni, via its subsidiary Agip Azerbaijan,

has funded a $2.25-million settlement project. According to Eros

Agostinelli, Agip's Resident Manager in Baku, the company got

involved simply because so much needed to be done. "Azerbaijan's

most serious problem is its large number of refugees," he

says.

Agip began addressing this issue shortly after it arrived in

Baku in 1995. Agostinelli explains the company's approach: "We

don't want to just spread money on the ground for the refugees;

we want to make an impact by putting that money toward a specific

project that will really make a difference in their lives and

improve their situation."

Most importantly, Agip didn't want to administer the project

themselves - they wanted an experienced NGO to coordinate the

various aspects of the project to ensure that they would be effective.

"Our first choice was UNHCR, the United Nations Organization

for Refugees and IDPs," says Agostinelli, "because

of its experience and operations all over the world. We thought

that establishing a partnership would become useful when similar

problems occur in other countries. Another reason we were looking

for a humanitarian organization was that we didn't want to give

money directly to the government and perhaps be perceived as

trying to gain influence."

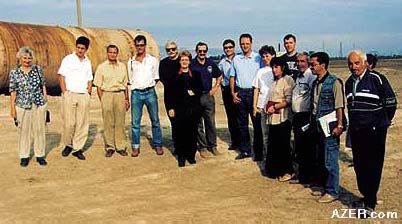

Above:

Diplomatic

delegation visiting the UNHCR / Agip Azerbaijan shelter project

in Khanlar which will house refugees from Kalbajar. The delegation

was led by Didier Laye, UNHCR Representative (4th from left)

and Eros Agostinelli, Manager of Agip Azerbaijan (9th from left)

and included the Italian and British Ambassadors and representatives

from the French and German Embassies and British Parliament.

Water storage tanks are in background. September 2000.

Accountability

UNHCR doesn't carry out all of the work for this massive project-it

contracts with other NGOs in Azerbaijan, using their expertise

in specific areas. UNHCR, under the direction of its Representative

Didier Laye, then reports back to Agip on the progress that has

been made.

Viewed as a "key study" by Eni, the project was begun

in 2000 after Agip and UNHCR came to an agreement on exactly

what it would do. "This wasn't the type of donation where

we give them the money, and then they do what they believe is

best," Agostinelli says. "We had to agree on all aspects

of the project. As far as I know, this type of partnership was

a first for Azerbaijan."

Azerbaijan's government-specifically Ali Hasanov, the Deputy

Prime Minister for Refugees-also had a say in the project, Agostinelli

explains. "We didn't want to do something that the government

didn't agree with. First, the initiative came from us and UNHCR.

Then the government made suggestions and recommendations as far

as where the project should be implemented and which refugee

populations needed the most help. That way we had all of the

parties on board."

Funds are dispersed according to a pre-agreed schedule that has

to be matched by project advancement. Agostinelli describes how

it works: "UNHCR has to give us evidence of what work has

been done and how the funds were spent before we release more

money."

Left: Bombed-out home in the Kalbajar region

of the Caucasus mountains. Azerbaijanis fled this region in Spring

1993. Many of them were able to find shelter only in what used

to be a pig farm where they have been living ever since. Thanks

to Agip Azerbaijan which has just undertaken a $2.25 million

shelter project that the UNHCR is coordinating, some of these

same people have been invited to live as a community together

in new shelters in the Khanlar region. From that location, they

can view the mountain range which used to be their home. Left: Bombed-out home in the Kalbajar region

of the Caucasus mountains. Azerbaijanis fled this region in Spring

1993. Many of them were able to find shelter only in what used

to be a pig farm where they have been living ever since. Thanks

to Agip Azerbaijan which has just undertaken a $2.25 million

shelter project that the UNHCR is coordinating, some of these

same people have been invited to live as a community together

in new shelters in the Khanlar region. From that location, they

can view the mountain range which used to be their home.

New Settlements

Originally, the plan was to build only one settlement site, in

Khanlar. "Then we decided to divide the number of shelters

between two sites, because one site would have been too large,"

says Agostinelli. "It would have made a huge village - much

too difficult to manage."

Agip, UNHCR and the Azerbaijani government decided it would be

better to build two refugee settlements, one in Khanlar and the

other in Beylagan, each with about 200 shelters. If four to five

people are assigned to each shelter, close to 2,000 refugees

will be housed.

Agostinelli believes that these smaller communities will be much

more manageable: "First you start with a limited amount

of people and create a core community. They start to work, and

then eventually others join them. The entire community grows

in phases. Whereas if you did it all in one go with more than

1,000 people, it would hard on everybody. This way there's a

better chance that it can be managed well and that the people's

needs will be met."

The first phase of building shelters has now been completed in

both locations. UNHCR used the services of Relief International

for what is called the "hard sector" - shelters and

other physical facilities. Relief International, based in Santa

Monica, California, has had experience with building similar

refugee shelters.

But the project entails much more than just housing, Agostinelli

points out: "We agreed with UNHCR that the project should

not be focused on only one aspect, building houses. It will have

much more of an impact if it's combined with 'soft sector' assistance,

'soft' meaning health, education, vocational training, income

generation activities and loans. NGOs like International Rescue

Committee (IRC) are more involved in these aspects of the project."

Tough Decisions

With only 200 shelters being built, obviously not all of the

Azerbaijani refugees who need help will benefit from the project.

Deciding who does gets assigned to these shelters is not an easy

task. "Unfortunately, there are a limited number of houses

available," Agostinelli says, "and many people will

be disappointed. That's why it's very important for us to try

to be as fair as possible."

UNHCR has the responsibility of choosing families for the new

shelters, based upon principles set forth by Agip. Top priority

was given to families living in the worst conditions, especially

those led by single mothers. Secondly, no one was forced to move

if they were unwilling. Finally, established communities were

to be kept intact as much as possible. For example, refugees

who lived together in the same cattle farm were to be given houses

close together so that their original community would not be

dispersed.

To find the neediest candidates for the new shelters, a team

from UNHCR, Relief International and IRC conducted a survey.

Maryam recalls: "When we started the survey, we were given

a list of the 300 families who had requested to move. But we

didn't rely on the list. We went and spent time amongst the refugees

and discovered that some of them who were living in the most

pitiful conditions didn't know anything about the project. They

weren't even on our list. So obviously we had to make changes."

NGO representatives found that refugees were living in sub-human

conditions: abandoned pig farms, the locker rooms of an abandoned

stadium, mud brick houses. In particular, they sought out refugees

who had been disabled during the Karabakh war, families who had

a lost a son or the head of the household or families that had

many children. Kalbajar families often have four to five children

each, sometimes spaced only one year apart.

Meeting Resistance

Surprisingly, some of the families who needed the most help were

the most reluctant to move. Maryam remembers: "For some,

it took a great deal of convincing to persuade them that we were

offering them something beneficial. Their solidarity was amazing.

If one Kalbajari said, 'No, I'm not moving,' then often the whole

group said, 'We're not moving either.'"

But they had their reasons. Primarily, they wanted to stay close

to their lifeline of family and friends. After all, more than

anything else, that's how they have had survived throughout this

tragic decade. In one case, five or six refugee families who

were all related to each other didn't want to move. One man told

the NGO representatives, "My wife and I are teachers. I'm

afraid that we won't find work at the new settlement."

A female relative agreed, "If everyone else in the family

moves, I'll move. If they don't, I won't either."

Of course, moving creates uncertainty even under the best circumstances.

The refugees wanted to know what the new conditions would be

like. For instance, refugee camps often have a shop where refugees

can buy food on credit; moving to a different location might

mean not being able to feed the children when cash is scarce.

Or perhaps the refugee family knows a doctor in a nearby town

who is willing to treat their children without being paid right

away. At the new settlement, who could they depend on for help

in the case of a medical emergency?

Also, refugees have come to rely upon the humanitarian aid that

is doled out at the camps. Perhaps they receive free bread or

flour once a month - would they still receive it in the new settlement?

A Better Life

NGO representatives tried to allay their fears by showing them

photos of the shelters and explaining how much land each family

would receive. When shown a panorama of the Khanlar site, refugees

from Kalbajar recognized it as the land where they used to graze

their animals, not more than 20 km away from their original home

on the other side of the mountain.

Just because the land is familiar to the refugees doesn't mean

that they automatically feel secure moving there. Even though

there is a cease-fire in place, refugees wonder what will happen

in the future. Will they be forced to flee again someday?

After asking a lot of questions and seeing photos of the new

shelters, it was often the wives who convinced their husbands

that it was the right decision to move. "I discovered that

the women played a great role in the family," says Maryam.

"The men automatically said, 'No, why should we become a

displaced refugee for the third time? We're going to stay here.'

But the women would ask more questions, such as, 'Would we have

clean water? How much land would we receive? Is there a school

there?' We found that if we could convince the woman, then they

would persuade their husbands."

Some refugees requested changes in the master plans, she says,

which shows a sense of initiative and leadership. "At first

we had to address all of their concerns in the hard sector. We

ended up modifying many things on the site - little things, like

the design of the daycare or the location of the bathhouse. Sure

- a bathhouse is a bathhouse. Naturally, any bathhouse would

be much better than what they had. But if you put the bathhouse

right in the middle of the settlement, some refugees would be

too shy to use it. So we changed its location, making it more

discrete."

Part of the appeal of the new settlement is its dual water system.

Maryam explains: "The refugees will have access to potable

water from a pipeline going from the Lake Goy Gol to Ganja -

it's very good quality water. The authorities in Ganja have authorized

us to extract water from the pipeline, and the refugees will

have about 300 tons. Actually, that's a huge amount. We have

never been able to do this before for any settlement. They will

have a dual system - one will feed the settlement by gravity,

the other one by pump and electrification."

Sustainability

As the shelters are completed, UNHCR will also put "soft

sector" resources into place to help the new communities

support themselves. Assistance with agriculture, education, health

care and small businesses is crucial for building a sense of

community, Agostinelli believes. "The success of this project

must not be judged only on the shelters that have been built

but also on the long-term development of the community. The responsibility

for a donor and for a humanitarian organization is to try to

set the right conditions for a settlement to develop sustainability."

Agostinelli describes the various ways that UNHCR and the NGOs

will help build a thriving community. "We've already made

plans to give the settlements medical facilities, medicine and

equipment. Then, within the community, they'll try to identify

the people who have had training in nursing. They'll give them

more training so that they can run the clinic. For the schools,

they'll find the teachers in the community and give them training

to teach." The project will also provide furniture for the

schools, books, educational materials and vocational training.

"For the micro-credit loans," he says, "they'll

identify people in the community who are willing to start their

own small businesses. They'll give them training in the type

of business they want to undertake, and then give them a small

loan to purchase the equipment that they need, to get them started."

Fighting Donor

Fatigue

After eight years of supporting thousands of refugees, international

donor support has been declining in Azerbaijan. Maryam theorizes:

"I think most people from the outside get tired of hearing

about the refugees - especially ones who have been made homeless

in their own countries. And I think these people themselves get

tired of asking for help. You can read it in their eyes. If you

only give them the opportunity, they can be better than many

of us. They have great potential - they've just lost their dignity."

Like several humanitarian projects in Azerbaijan, the Agip settlement

project is designed to help Azerbaijanis eventually become self-sufficient.

Vugar explains why this philosophy is so important: "You

can't go on forever giving people food and blankets. You don't

want to make these people dependent on you, so that they're just

sitting around idle. At the end of the day, you don't want to

have a guy with an outstretched hand.

"We believe that there will be a day when these people will

be able to leave these shelters and go back to their land of

origin. But until that day comes, these people have the right

to live in decent conditions."

For Agostinelli, figuring out what goes into making a sustainable

village is a new experience. "I've never dealt with the

humanitarian sector before. It's a fascinating process. You really

have to put a good deal of effort into it to guarantee that it

will really turn out right. But it's an important sector for

us because, as an oil company, we often work in developing countries

that have great social problems. Establishing good community

relations by undertaking worthy projects is important to our

business."

Other UNHCR representatives who contributed to this article include

Ulvi Ismayil, Senior Field Clerk; Naila Velikhanova,

Senior Field Clerk; and Nijat Karimov, UNHCR Field Offshore,

Barda Office Manager.

____

From Azerbaijan

International

(8.4) Winter 2000.

© Azerbaijan International 2000. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 8.4 (Winter 2000)

AI Home

| Magazine Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|