|

Autumn 2000 (8.3)

Pages

16-19

From Pilaf to Pizza

A Road

Map of Azerbaiijani Cuisine

by

Tahir Amiraslanov

Above:

Making kabab

on a "mangal" grill. Photo: Huseinzade

"What is Azerbaijani cuisine?" This is the question

that has come up repeatedly as we worked on this issue. Does

it include the foods that Azerbaijanis ate before the Soviets

came to power? Today, many of those dishes are no longer prepared

in the Republic, or they're only eaten on occasion, like rice

pilaf. Or is Azerbaijani cuisine based on the foods that Azerbaijanis

ate during the Soviet period? Many of these dishes, like cabbage

dolma, are Russian or Russian-influenced. What foods can Azerbaijanis

claim as their own?

One thing is for sure: Azerbaijani cuisine has changed dramatically

over the past century due to political and economic influences

that were often beyond the control of Azerbaijanis themselves.

And this dynamic process is still very much alive today. Food

expert Tahir Amiraslanov discusses some of these past and present

changes, explaining some of the evolution that is taking place

in Azerbaijani cuisine.

During the Soviet period, Azerbaijan's state employees and students

ate in free, government-run cafeterias. Nutritious meals were

prepared every day, freeing Azerbaijani women from housework

by enabling them to spend less time cooking for their families.

In general the dishes that were prepared were the same in cafeterias

throughout the Soviet Union: meat cutlets, goulash, borscht and

shi (fish soup), plus a few national dishes. Such standardization

was one of the ways that the Soviet government set out to create

one Soviet people.

The phrase "you are what you eat" rings true, since

food is an important part of one's culture and sense of nationality.

The Soviet leaders were determined to shape the psychology and

behavior of all Soviet citizens in order to create the new Soviet

man. Therefore, basically the same food was served to all of

them. Primarily, it was created on the basis of Russian cuisine.

_____

Russian Influence

As a result, Azerbaijani cuisine underwent considerable changes

during the Soviet period, and a number of Russian dishes were

included as everyday fare. For instance, in pre-Soviet Azerbaijan,

we didn't have the Russian "Stolichniy" salad (potato

salad with shredded chicken, carrots and peas in a mayonnaise

base). We also didn't have the Russian salad vinegret (beans,

potatoes, carrots, pickled cabbage and beets). But now we have

accepted these salads and consider them our own, even to the

extent that we serve them at wedding parties and other special

occasions.

Prior to the Soviet period, alcohol was not usually served at

Azerbaijani wedding parties. But because of the Russian influence

and the decrease of Islam's significance during the Soviet period,

alcohol became the norm, especially at wedding parties - at least

among men. Also, we Azerbaijanis are now more likely to follow

the Russian pattern of serving cake for dessert (or ice cream,

too, as in the West), rather than our own national pastries like

shakarbura or pakhlava (baklava).

Today, we no longer

have a system that provides free food to employees and students.

Most large factories have closed down and because wages are low,

most people can't afford to eat in restaurants. Along with independence

came bread lines - especially during the early years of our freedom

in the 1990s. You can't blame the Soviet Union, as this was a

phenomenon characteristic of the post-Soviet period and was experienced

throughout all of the 15 former republics. During the Soviet

period, commodities were much cheaper. A monthly salary was sufficient

to support a family and even entertain guests. Today, we no longer

have a system that provides free food to employees and students.

Most large factories have closed down and because wages are low,

most people can't afford to eat in restaurants. Along with independence

came bread lines - especially during the early years of our freedom

in the 1990s. You can't blame the Soviet Union, as this was a

phenomenon characteristic of the post-Soviet period and was experienced

throughout all of the 15 former republics. During the Soviet

period, commodities were much cheaper. A monthly salary was sufficient

to support a family and even entertain guests.

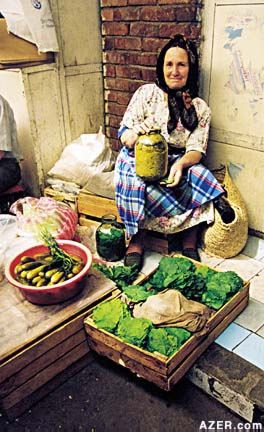

Left: Vendor selling pickles

and grape leaves that are both fresh and in brine at one of Baku's

central markets.

These days you can find anything you want in shops-for a price,

that is. But not everyone can afford them. Some Azerbaijanis

eat little more than bread and water, while others enjoy expensive

dishes of meat and fish daily. During the Soviet period, many

food items were available, but you had to pay "under the

counter" (in Russian: "iz-pod poli"), especially

for items like bananas, Indian or Ceylon tea and sweets from

Moscow. Products like cheese were usually always available in

the market, but if you wanted foreign cheese - Bulgarian, for

example - you had to buy it "under the counter". Some

products were sold with coupons, including butter, sugar and

meat. But then during Perestroika (1980s), food shortages began,

especially with items like butter.

Foreign Foods

These days, it seems foreign products and cuisines are more prominent

than our own national dishes - at least in restaurants. Foreigners

tend to eat in restaurants that feature cuisine from Turkey,

the U.S., China, India, France and the U.K. Now that we have

access to a wide variety of cuisines, these dishes are becoming

more popular among us as well.

Turkish restaurants in particular have captured the market in

Azerbaijan. Frankly, our local businessmen can't compete with

them because we haven't truly sensed what it means to work according

to the rules of a market economy. In the restaurant business,

economic and legal matters are much more complex than simply

setting up a kitchen.

Many new foods, especially "fast foods", imitate European

and American styles, such as hamburgers and hot dogs. We had

fast foods during the Soviet period, too, only they were Russian

snacks. On any street, you could buy "pirozhki", a

type of dough stuffed with potatoes, peas, rice or meat, or "blinchiki",

pancakes stuffed with meat or cheese. One of the advantages of

being exposed to these foreign influences is that we are exchanging

new information and adopting new technology. For example, we

are beginning to use Iranian equipment to prepare flatbreads

like "lavash" or "yukha".

Import / Export

During the Soviet period, many of our food products were brought

in from other Soviet republics or from Eastern Europe. For example,

condensed milk and sugar came from the Ukraine, butter from Russia,

chickens from Hungary, green peas and cheese from Bulgaria.

Azerbaijan, in return, supplied a great deal of vegetables and

fruits. For example, Lankaran, which is near our southern border

with Iran, was considered to be the vegetable garden of the Soviet

Union. It also produced citrus fruit. Azerbaijan also supplied

cabbage, grapes, fish, canned fish, canned fruit, alcohol and

wines. One wine - Aghdam - became so notoriously popular among

Soviet drunks that the name even entered Russian folklore. Aghdam

is a city in the central part of our country, which these days

is under occupation by Armenian troops. But the wine that took

its name from Aghdam was a cheap variation that made people get

intoxicated quite quickly. A Russian expression claims: "Agdam:

nikomu ne dam," meaning "Aghdam: I wouldn't offer it

to anyone!" Of course, we had other very fine wines and

our vineyards flourished.

Today we import much more food than we export. We export caviar

and sturgeon, but in a very limited quantity, whereas we import

beef from the Ukraine, Russia and Poland, potatoes from Poland,

chicken from Iran and bottled water from Switzerland. Much of

our butter is imported, too, as are tropical fruits like banana

and kiwi. Since there are so many imported products, our own

agricultural efforts have suffered.

Below: Author Tahir Amiraslanov

(on extreme right) with chef colleagues of Azerbaijan's Culinary

Center who often participate in international food competitions.

Azerbaijanis need to

start supporting locally produced goods. Importing is not good

for our economy. Azerbaijanis need to

start supporting locally produced goods. Importing is not good

for our economy.

When a country exchanges its currency for foodstuff, it only

becomes poorer. This is not a rational use of our money. Azerbaijanis

should "Buy Azerbaijani" and use fresher, local products

that support our own agricultural efforts.

Food Quality

Quality control is another challenge for Azerbaijan's food industry.

The quality of foodstuffs seems to be deteriorating. For instance,

if you compare the eggs produced by hens cooped up in cages with

those that roam freely in the villages, you'll discover a pronounced

difference in the color of the yolks. They're pale yellow instead

of the red-orange that we were used to.

It used to be that when the Soviet Union bought and imported

products, there were several control checks: in the exporting

country, on the border and inside the country itself. All of

the goods had to meet certain standards. That's why imported

goods were considered to be of high quality, whether they were

oranges, tangerines, tea, bananas or wheat from the U.S. Azerbaijan

doesn't have all the necessary equipment or the necessary agents

for checking, so lots of smuggling goes on. Who is there to check

these items and protect the consumer?

Reclaiming Traditions

Despite this movement toward more international, imported foods,

there is another significant trend in Azerbaijan-to return to

past traditions. For example, in both Lankaran (near the Iranian

border) and Shaki (in the northwestern part of Azerbaijan at

the foothills of the Caucasus), farmers are beginning to plant

fields of rice again. Even though rice is a very traditional

food-Azerbaijanis in Iran eat it every day-we haven't produced

it for quite some time. Subsequently, rice became a dish reserved

for special occasions for us during the Soviet period.

Disappearing Foods

Even though there is a tendency towards traditional foods, many

Azerbaijani dishes are disappearing. Part of this has to do with

the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Approximately 20 percent of Azerbaijan's

territory is now under control by Armenian forces. Those lands

were famous for their agricultural output and represented at

least one-third of our national production.

Between 1988-1990 approximately 200,000 Azerbaijanis fled Armenia.

Then an additional 800,000 had to flee regions within Azerbaijan

itself, such as Nagorno-Karabakh and the surrounding territory.

The trauma that results is not limited to the effects brought

on by psychological, economic and geographical displacement.

It means that people are being cut off from their cultural roots

as well, including their traditional food practices. For example,

there's a type of stuffed cabbage or grape-leaf dish known as

"kor dolma" or "yalanchi dolma". It means

"false dolma" because the stuffing contains greens

and grains without meat.

Kor dolma exists in other regions, but the version made by the

Azerbaijanis who lived in Armenia had its own unique characteristics.

Refugees are also forgetting their unique regional cuisine from

the Karabakh regions. It's been nearly 10 years since many of

them were forced to flee - often with little more than the clothes

on their backs. Today, living in refugee camps, they don't access

to the necessary ingredients to prepare the foods that they used

to eat on a daily basis. These days, sometimes they can barely

find bread to eat. In summer, many of them are living only on

tomatoes and bread.

So how can refugees from the Karabakh region prepare "girkhbughun

pilaf"? This regional dish calls for special wild greens

that are indigenous to the region. How can refugees prepare it

if they don't have access to these plants? They'll soon forget

how to do it.

And then there are the refugee grandmothers who are passing away,

unable to survive the harsh conditions of refugee life. Much

of their knowledge about these foods is not documented. If these

patterns continue, the next generation will not even know what

their own native cuisine tasted like.

Nearly Obsolete

Some traditional foods seem no longer to have a place in Azerbaijan.

One example is "gutabs" (turnovers) made from camel

meat. This Azerbaijani dish used to be very popular in Baku up

until the 1960s when the camels disappeared. Now there are only

a few wild camels left in the region of Davachi, about three

hours north of Baku on the Caspian coast. There are also several

breads that are disappearing. It used to be that Azerbaijanis

in every region would prepare a small bread called "galach"

for the holidays. But I haven't seen it lately in any of the

regions.

Another bread is called "takhta" (meaning "board"

in Azeri). This bread becomes tough as a board, but softens when

added to broth or water. Ancient merchants from Shamakhi and

Shirvan used to prepare this bread for long journeys. It had

a very pleasant, sweet taste. But after the 1950s-60s, Azerbaijanis

no longer had any need for it. "Saalab" is a thick,

jelly-like drink made from milk and the roots of the wild saalab

plant (orchis in Latin). It's a warm beverage that used to be

very popular in Azerbaijan. You could buy it from street vendors

who kept it hot in samovars. But you rarely see it these days.

During the Soviet period, not much attention was paid to the

development of native Azerbaijani cuisine. But now that we are

independent and no longer living under the domination of any

nation, we are the ones who must keep Azerbaijani cuisine alive.

Perhaps one day there will be a movement among Azerbaijanis themselves

to rediscover and embrace their own native foods-hopefully before

more of them become extinct.

Tahir Amiraslanov is General Director of the Azerbaijan

National Cookery Center, a Member of the International Judging

Board, and Vice President of the Russian Cookery Experts Association.

He was interviewed by Arzu Aghayeva on AI's staff.

_____

From Azerbaijan

International

(8.3) Autumn 2000.

© Azerbaijan International 2000. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 8.3 (Autumn 2000)

AI Home

| Magazine Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|