|

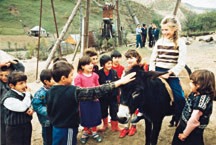

Summer 1998 (6.2) Basgal and Lahij Photos by Oleg Litvin

Photo: Lahij is famous for coppermaking. Both are very old and difficult to reach, but their populations are quite different from one another and from other Azerbaijani mountain villages. One important difference is that the people in Lahij speak Tat, a Persian language, but the people in Basgal speak a Turkic language. If you've already traveled the four plus hours from Baku and braved the treacherous narrow mountain road to visit either Lahij or Basgal, it's worthwhile to take in the other village as well so that you can see just how unique they are. Basgal Everywhere there are stone pavements and cobbled roads. The houses are not like village cottages surrounded by big gardens or yards; rather they are multi-storied houses, much like city buildings. Most of them have balconies. The streets are narrow and winding, with barely enough room for one car to drive through.

Each quarter of the village has its own water source, as there are no wells there. Mountain water that comes from springs further up the mountain is referred to as "light water" because it is more filtered and tastes better. Unfortunately, not every quarter of Basgal has easy access to "light water." Zulfugar bey, who is originally from Basgal and now lives in Baku, spoke about the lack of agriculture in Basgal. He said that people usually plant a few flowers in their yards or have one tree in their courtyard. All kinds of produce, even eggs, have to be imported from outside. Once a week there is a big market in the center of Basgal where people from neighboring villages come and sell food. Zulfugar bey remembered: "We would always distinguish ourselves from those who came from other villages. To us, they were 'villagers;' we never really considered ourselves 'villagers.' Only after I came to Baku did I realize that we were villagers, too." Basgal used to be famous for its silk industry. Some people believe that it was Basgal that made Azerbaijan's silk especially "kelagays"-world-famous. Ancient silk-weaving machines are still kept in some Basgal houses today. There are two mosques in Basgal: one dates back to the 11th century, the other to the 14th century. Near the older mosque stands a huge tree that is supposedly 900 years old. It is so large (7 meters across) that there used to be a "chaikhana," or teahouse, in the cavity of the tree. The chaikhana has since been closed for fear that it might cause damage to the tree. The village's bath house dates

back to the 16th century. There is a legend that this bath house

is heated by only a single candle. In fact, there is only one

oven where wood is burned for heating the water. The amazing

thing about this bath house is that the oven not only heats up

the water; the heat somehow gets underneath the floor and heats

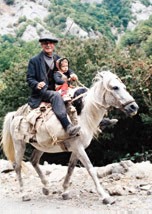

the whole bath house. Lahij Lahij is surrounded by tall mountains that are layered with limestone, sandstone and clay. Stone from these mountains was used to build most of the houses in the village. Once in town, you'll probably notice that the houses seem to have been placed there randomly, without any set plan, along the narrow and winding cobblestone streets. All of the houses have flat roofs, and some feature balconies that look out onto the street. If you get a chance to step inside one of the small courtyards, you'll be likely to see a "tendir," which is an oven used for baking bread. On the other side of the courtyard, you'll usually find a stable or a chicken coop. Inside the houses, you'll find a heating device called a "kursu." A kursu is a big table placed above a kerosene stove or hearth and covered with a big blanket. In the winter, the entire family gathers around the kursu to stretch out their legs and warm their feet. Even families that are financially secure who use fireplaces to warm their guest rooms, put a kursu to warm their own family's room.

Why is Lahij so different from its neighbor village across the way? Local legend tells that Iranian Shah Kay Khosrow retired to this village in the Caucasus because of its pleasant climate and picturesque scenery. The people consider themselves to be Persian in origin, in particular descendants of Kay Khosrow's original court, and say that the village was named after a place called Lahijan in Persia. They maintain that the Shah died and was buried in Lahij. In the Zavara cemetery, there's even a grave with a tombstone that clearly reads "Kay Khosrow," along with other tombstones that date back more than 1,000 years ago. Perhaps a 1,000-year-old tombstone doesn't seem out of place in such an ancient village. Such an artifact fits an observation made about Lahij in a recent U.N. report about Azerbaijan: "Lahij has preserved its communal harmony and social cohesion across the centuriesThe spirit of the Middle Ages still lingers there."

|