|

Winter 1997 (5.4)

Pages

28-31

Piecing Together

History, String By String

The Reconstruction

of Azerbaijan's Medieval Instruments

by Jean Patterson

Related Articles

1. Music

Therapy

- What Doctors Knew Centuries Ago by Farid Alakbarov

2. Traditional

Instruments:

Majnun Karimov Brings Medieval Music to Life

Click here to hear a sound sample

By studying manuscripts

and miniature art, musicologists have discovered that more than

60 different string, wind and percussion instruments existed

in ancient and medieval Azerbaijan. By studying manuscripts

and miniature art, musicologists have discovered that more than

60 different string, wind and percussion instruments existed

in ancient and medieval Azerbaijan.

Photo: The National Ensemble of Ancient Traditional

Musical Instruments in front of the Shirvanshah Palace in the

Inner City (Ichari Shahar). The musician's costumes are based on 14th century

miniature paintings.

They

know the names of most of these now-extinct instruments, such

as the "chang" mentioned by Azerbaijani poets like

Nizami. (The "chang" is featured on the cover of this

issue.) Until now, however, many details about these instruments

have eluded historians.

For the past 25 years, Azerbaijani musicologist Dr. Majnun Karimov

has been searching for the answers to questions about what these

instruments looked and sounded like. Through careful research

and study, he has literally pieced together a portion of Azerbaijani

musical history by recreating some of these ancient instruments.

1

Thanks

to Karimov, instruments such as the chang, barbat, chogur and

rubab can now be heard once again.

Chang and Barbat

One

of the greatest thrills in Majnun Karimov's music career took

place in 1988 at the 500th Jubilee (birthday) of Shah Ismayil

Khatai2 when an ensemble o

f musicians performed on medieval instruments that he, himself,

had reconstructed. It was a dream come true for Karimov to recreate

the sweet, melodious sounds of stringed instruments so that a

contemporary audience could appreciate. His work has become a

major contribution to the cultural history of Azerbaijan.

Majnun first

became interested in folk instruments as a young boy when his

mother brought her father's tar to their home. Mostly, it hung

on the wall in his house, but from time to time, his father would

take it down to play. Later, Majnun's father bought him an accordion.

His serious research on traditional Azerbaijani instruments began

in 1972 after he graduated from the Baku Music Academy. At that

time, he began searching the classical writings and art miniatures

for clues that would unlock the musical secrets of the past.

For several years, he researched the manuscripts at Azerbaijan's

National Manuscript Institute. Eventually in 1995, he completed

his Ph.D. thesis on "The Ancient Stringed Musical Instruments

of Azerbaijan."

Left: Chang, Center: Barbat, Right: The

National Ensemble of Ancient Traditional Musical Instruments

performing inside the Shirvanshah Palace in the Inner City (Ichari

Shahar) in Baku.

First Attempt

Karimov's

first attempt at building a replica was for the " rud "

(pronunciation rhymes with "food"), a large-bodied,

four-stringed instrument made partly of wood and partly of leather.

Similar to the "ud," the neck of the rud is longer.

The process took several months after much trial and error. "Sometimes

the measurements weren't right," Karimov confesses, "and

I would have to disassemble the whole thing and start all over

again. It took me so much time to prepare the strings which were

supposed to be made out of gut and silk thread using a special

technique. Then I had to figure out how to adjust them. Finally,

I was able to play it. The "rud" had such a beautiful

timbre reminiscent of a very old sound. It inspired me to push

on to work on other instruments."

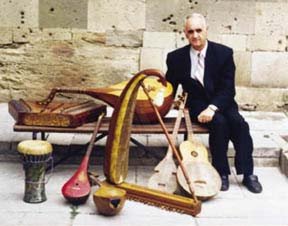

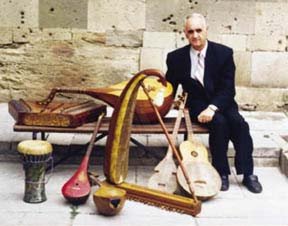

Left: Musicologist Majnun Karimov with eight of the

ancient instruments he has reconstructed. Left: Musicologist Majnun Karimov with eight of the

ancient instruments he has reconstructed.

And so he did.

Nine early instruments, completed during the 1980s, are currently

on display in the Ethnic Instruments Department of the State

Museum of Azerbaijani Musical Culture.

Thanks to Karimov's efforts, a special laboratory was opened

in 1991 at the Baku Music Academy to "restore and improve

old musical instruments."

Karimov insists that many factors must be considered when building

these instruments including the correct choice of timber, its

seasoning and moisture content. Even the time of year when the

tree is felled must be taken into account. The sap is lowest

in January and February. Wood that is full of sap can develop

cracks as it dries. Karimov notes that wood that has dense annual

rings produces a stronger sound.

There are two

ways to assemble instruments according to Karimov. One is to

fashion the parts separately and put them together as with the

"barbat." The other method is to plane a block of wood

down to the correct specifications as is done with the chang.

It's much easier to plane wet wood. Afterwards, the roughly hewn

wood is allowed to dry for a long time at a specific temperature.

A few years later, the wood is worked again. Finally, the frets

and stem are attached.

Karimov has found that the strength of the wood is particularly

important for the neck and fingerboard because of the pressure

caused by tuning. The fingerboard can become distorted if the

material is not strong enough. He recommends walnut and pear

pegs because they can withstand atmospheric factors of humidity

and temperatures and maintain stable tuning.

Various species of trees are used for these old instruments including

mulberry (Morus alba), walnut (Juglans regia), red willow (Salix

acutifolia), pear (Pyrus communis) and apricot (Prunus armenica).

The strings are mostly made of silk, horsehair or animal gut.

Sounding boards are usually made of mulberry or walnut and those

covered in leather create the greatest resonance. In addition

to sheep skin, sometimes fish skin, the Absheron gazelle skin

or even the inner lining of an animal heart is used.

Early Music

Evidence

shows that stringed instruments were common in ancient Azerbaijan.

Archeological excavations in the village of Shatirlar near the

city of Barda uncovered an earthenware piece dating between the

4th and 3rd century B.C. depicting a woman playing an instrument

similar to the chang.

Much of what we know about Azerbaijan's musical heritage during

the Middle Ages comes from folklore and classical poetry. Important

examples are the writings of poet and philosopher Nizami Ganjavi

(12th century), the poet Fuzuli (16th century) and the studies

of eastern musicologists Urmavi (13th century), Maraghayi (14th

century) and Navvab (19th century).

Maraghayi was

especially interested in the restoration and improvement of stringed

musical instruments. In his work "Magasid Al-Alhan,"

he provides information about numerous musical instruments such

as: udi gadim (old ud), udi kamil (improved ud), shashtay, kamancha,

jiganak, Shirvan tanbur, Turkish tanbur, rubab, shidirgi, shahrud,

mugni and nuzha.

Musical instruments were also depicted in miniature paintings

made by artists of the 16th and 17th centuries, such as Sultan

Muhammad Aga Mirek, Mirza Ali, Muzaffar Ali and Mir Sayid Ali.

These tiny pictures have become important documents for reconstructing

these instruments.

The question is always asked: What happened to these early instruments?

Innovation and changing times brought the demise of some of these

instruments. In other cases, instruments were adapted to fit

the needs of the time and older designs were replaced by new

ones. In some cases, a completely new instrument evolved. Many

musicians think that the "tar" originated from the

"chogur." The chogur had 22 frets and was used between

the 12th-18th centuries. Research shows that the chogur's assemblage

and sound structure of these two instruments were very similar.

Mirza Sadig Assadoglu ( Sadig -jan) modified the five string

tar to 13 strings. After his death in 1902, it was simplified

to 11 strings.

Chang and Barbat

Two

examples of instruments that Karimi has rebuilt are the chang

and the barbat. The chang is the forerunner of the harp and seems

to have been used extensively in medieval Azerbaijan. Some believe

that the chang was derived from a hunting weapon, such as a bow.

Its sounding board seems to resemble a fish. Like the harp, the

chang is plucked with the fingers of both hands.

Maraghayi wrote that the chang had leather stretched over the

sounding board, and that the strings, sometimes as many as 24,

were made of threads. In his article "Music and Dances of

the Ancient Turks," Dr. Faruk Sumer, who has studied the

ancient musical instruments of the Turkish peoples, mentions

that two changs were found during the excavation of the Altay

grave site in Turkey dating to 250-500 B.C. Legend suggests that

the chang was created by the Almighty. Actually, in some early

drawings, the chang is depicted as a holy angel.

The barbat is a member of the lute family, a pear-shaped stringed

instrument. Miniatures by the artist Mirza Ali show that its

body was bigger than that of the lute, and that it had a long

neck. Written sources tell us that the barbat was played much

like the ancient lute, although tuned according to different

intervals. The 12th century Azerbaijani poet Afzalagdin Khagani

wrote that the barbat had eight strings, was made of animal gut

and had four sound openings, called "four little stars."

Musicologist T. Vyzgo describes it as having an Arabic derivation,

originally called an "al-ud."

The barbat was chiefly played at palace feasts, often along with

the chang. Nizami describes the chang and the barbat as complementary

instruments: "Nekisa took up her chang, Barbad took up his

barbat. And the sounds resounded in winged harmony like a rose

in harmony with both color and fragrance. Barbat and chang, intoxicating

and robbing one's strength."

More Music to Come

It's

possible to hear these instruments being played again today in

Azerbaijan by the Ancient Instruments Ensemble, a group created

by the Folk Instruments Museum in 1996. Karimov is the director

of this 12-member ensemble. The group's repertoire includes folk

melodies as well as music written down by Urmavi and Maraghayi,

in an alpha-notational system based on what is known as the ABJD

system (pronounced "ahb-jad" which rhymes with the

word, "pad") . These four letters name the sequence

of first letters in the Arabic alphabeta lef, beh, jim, dal.

Each note was represented by a single letter or a letter combination

. For example, note 1 was "A," note 2 was "B,"

note 3 was "J," etc. As the progression continued,

letters were written in combination, such as "AA,"

"AB," "AJ," etc. Duration of notes was also

indicated.

With great effort, Shamil Hajiyev, a musicologist associated

with the Ensemble, has adapted a music computer program to transcribe

the alphabetic notational system and convert it into a melody

line.

To learn one of the old melodies, the members of the Ancient

Instrument ensemble listen to the melody line played on his computer

laptop and improvise the harmony for their various instruments.

Needless to say, it's a long and tedious process. English composer

and musicologist George Farmer (1882-1965) has also researched

Urmavi's works and deciphered some of these early melodies.

Work continues at Karimov's laboratory, as more ancient instruments

like the "golcha gopuz," the "nuzha" and

the "mugni" are being researched and restored. It is

Karimov's hope that research and restoration of the ancient folk

instruments will be able to continue until many of the mysteries

and harmonious sounds created in the past are available for contemporary

man to enjoy as well.

Majnun Karimov

is the

head of the Laboratory for the Reconstruction of Ancient National

Music Instruments, located in the basement of the Academy of

Music at 98 Shamsi Badalbeyli Street. Tel: (99-412) 98-69-72;

Home Tel: 91-95-48.

The Museum of Folk Instruments, located in the former residence

of the famous tar player, Ahmad Bakikhanov, is at Zargarpalan

119. Contact: Tapan Gaziyeva at (99-412) 94-60-62.

UP 1

The

medieval instruments described in this article are all stringed

instruments. They include barbat, chang, chogur, golcha gopuz,

gyjak, mugni, nuzha, rubab, rud, shashtay, Shirvan tanbur, shahrud,

shidirigi, Turkish tanbur , udi gadim (old ud ), udi kamil (improved

ud) and tar.

2 Shah

Ismayil was the founder of the Persian Safavid Dynasty (1501-1736).

An Azerbaijani, he lived in Ardabil (an Azerbaijani city located

today in Iran) and played a vital role in subjugating local tribes

and in unifying the fragmented Persian Empire. Shah Ismayil was

also the leader responsible for proclaiming Shi'i Islam the state

religion which, in turn, served to create a national consciousness

among the various racial elements of the region.

From Azerbaijan

International

(5.4) Winter 1997

© Azerbaijan International 1997. All Rights Reserved.

Back to Index

AI 5.4 (Winter 1997)

AI Home |

Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|